Chichester Festival Theatre is gaining a reputation for using large quantities of water in their productions to great effect. There are, however, many difficulties to overcome when water is used on stage.

In 2003, Chichester Festival Theatre famously produced a series of plays that all took on the theme of water. The Gondoliers, The Merchant of Venice, the UK premiere of The Seagull, and the world premiere of The Water Babies, creating new experiences for the audience, and using the watery effects to their advantage. The stage was transformed into a swimming pool – pumped with 9800 litres of water – interchangeable platforms that the actors could stand on. The audience were taken by surprise; the stage had been transformed into something other-worldly.

It was throughout this season that the Theatre built a relationship with a company called Water Sculptures, an organisation that first created water features for the motor industry, and later moved onto work with theatrical productions and major events. To inform their practise, they research techniques used by other industries that need to work with large quantities of water, such as horticulture. The Theatre first became aware of Water Sculptures after seeing a performance at the Royal Albert Hall, and has since worked alongside them.

To use real water on stage is not without technical difficulties. Any escaped water could potentially cause devastating damage to the entire set and backstage area. Mixing water and electricity is another main concern. For example, sprinklers that are required to make rain on stage have to be fixed below the lights in the rigging to avoid obstruction. As we’ll see, with so much to bear in mind, the solution to one challenge can in turn raise several more issues.

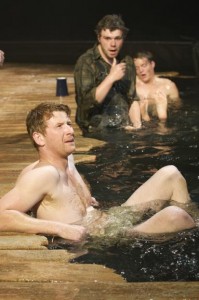

In 2009, the Theatre produced John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, directed by Jonathon Church. The story follows the Joads family who are driven from their home after a devastating drought forces their farm to be repossessed. Water is a main component of the story. A pool of water was present at the front of the stage throughout the play, yet it was only when one of the actors climbed in that the audience were aware of how deep it was. Towards the end of the play the Hudson River bursts its banks, and for this production, the stage was flooded. The creative team were faced with many obstacles, including finding a material that will be strong enough to hold the ten tonnes of water required for this performance. They solved this by installing a rubber lining underneath the whole stage which held the water in a manageable space, and could also be rolled away to make room for another play. However, this lining could only take a certain amount of weight without puncturing. This became particularly tricky when it came to building the truck that the Joads family was travelling in. To make things more complicated, this truck would be on stage during the flooding scene, so it also needed to be heavy enough so that it wouldn’t float as water levels rose.

The hit musical, Singin’ in the Rain, produced in 2011 and which famously uses 12,000 litres of water, also caused similar technical issues. During the title song, it should be raining on stage, but it was quickly discovered that this was surprisingly loud, and would overwhelm the actor’s voice. The team accepted that they would have to replace a large number of microphones that would be damaged due to the water. Water underneath the stage would have to be forced upwards at the same time that it was raining, in order to create enough of a pool for the actors to splash in quickly. The material for the floor had to be chosen carefully in order to be safe for the actors to dance and walk on. They chose a hollow plastic material commonly used in decking where the water could be drained when required. However, the amount of tap dancing that was in this production meant this flooring sometimes shattered. As a solution, long wooden poles were fed through the floor for support, with the steel components galvanised to prevent rusting.

The Theatre has just undertaken another challenge in the form of Neville’s Island, by Tim Firth (11-28th September 2013 Theatre In The Park) which encompassed the theme of water once more. The play involved rain, fog and mist to create the ’swamp’, a pivotal element to the story, with fantastic results!

Alice Du Port is a creative arts student at Bath Spa University who conducted work experience on the Pass It On project during summer 2013. Following her interest in set and costume design she spent her time researching and exploring these areas of the Theatre’s history.